AI fixes Ottawa

If HI (human intelligence) can't get the job done, let the robots try?

My column in the Ottawa Citizen this week asks ChatGPT for help solving three stubborn Ottawa problems. The full exchange with the tool is reproduced below, or you can read the human-written summary here.

Question: What’s wrong with traffic construction in Ottawa and how can we fix it?

Here’s a breakdown of what’s going wrong with traffic construction in Ottawa — and some ideas for how the city could fix it (or at least reduce the pain). I draw on recent reporting, audits, and what many local residents are saying (on social media and community forums).

✅ What’s the problem — why Ottawa’s construction is messing up traffic so badly

• Too many overlapping projects and constant lane/road closures

Every year seems to bring a new wave of construction: from road resurfacing to sewer-and-water-main renewals to multi-year transit expansion. As of 2025, many major roads (like parts of Stage 2 O‑Train / LRT corridors, and main roads like Highway 417, Bank Street, Greenbank Road / Baseline Road) are under construction. (Capital Current)

Because projects overlap in schedule and geography, traffic disruptions compound. For instance: lanes closed on the 417 while detours are active; local streets turned into arterial routes; sidewalks or bike lanes closed for extended periods. Many people complain the construction “never stops.” As one Redditor put it:

“My entire route this summer has had closed lanes, detours and delays.” (Reddit)

Some lane closures or restrictions persist long after the bulk of work seems done — contributing to bottlenecks and frustration. Example: reports of closed 417 lanes weeks after cement-barrier installation, even when little visible work is occurring. (Reddit)

• Poor coordination / planning: many projects + inadequate scheduling

According to the city’s own notices, lane reductions, alternating traffic and detours are “expected” for many operations, while still guaranteeing access for businesses, cyclists, pedestrians, etc. (City of Ottawa) But that doesn’t mean the flow works smoothly — many disruptions still create major delays.

After approval of developments or infrastructure projects, the post-approval process often bogs down. A 2025 audit found legal- and administrative-agreement processes (for subdivisions, site plans, etc.) dragging for hundreds of business days — delaying when construction can even begin, or causing clustering of many jobs at once. (Ontario Construction News)

For large transit projects like the LRT expansion, detours and lane closures are often unpredictable or frequent. Residents and small businesses complain about long-term disruption and unclear timelines. (CTV News)

• Negative impact on non-car users: pedestrians, cyclists, transit riders, local businesses

In some construction zones, cycling and pedestrian (“active transportation”) infrastructure is sacrificed or sidelined. For example, during LRT-related detours, “sidewalks or mixed-traffic” replacements are used instead of properly maintained multi-use paths, discouraging safe cycling / walking. (Bike Ottawa)

Transit reliability suffers: more buses stuck in jams, extended commute times, and hidden detours. One article discussing changes to OC Transpo transfer windows cites construction as a contributing factor to longer, more costly public-transit commutes. (Ottawa Lookout)

Small businesses along construction zones have seen reduced foot traffic or accessibility — some reports mention business closures or financial hardship during extended construction periods. (Capital Current)

• A public-perception & quality-of-life hit: frustration, unpredictability, inefficiency

Many locals on forums describe the situation as “chaotic,” “never-ending,” or “a disaster.” (Reddit)

Construction season seems to be dragging longer and becoming more severe (some say it now feels year-round). (Reddit)

For commuters, it often means unpredictably long travel times — even on routes that used to be manageable. (Reddit)

🛠️ How could Ottawa fix (or at least improve) the situation

Here are strategies — drawn from urban planning best practices and public feedback — that could ease the burden of construction while still allowing necessary infrastructure upgrades.

• Better scheduling and phasing: avoid overlapping major projects where possible

Spread out major road/infrastructure work so multiple big projects are not happening at once in nearby areas. This reduces compounded disruption.

Use “off-peak” hours / night-time work more often — especially for major closures. Many construction-management guides recommend this to minimize daytime traffic delays. (Traffic System Management Services | TSL)

Build buffer time into project timelines and coordinate across departments and projects so they’re not bottlenecked or conflicting (especially for permit or post-approval delays).

• Use “smart work zone” design & traffic-management technologies

Implement adaptive/dynamic traffic-signal timing (real-time traffic-sensing + adjusting) instead of static timings, to better manage changing flow around detours. This is a widely recommended method to ease congestion during construction. (Wikipedia)

Use concrete barrier-transfer machines (“zipper lanes”) or temporary barrier systems instead of long-term cone-based lane closures where possible. This helps preserve lane capacity and safety during construction phases. (Wikipedia)

Provide real-time traffic information to drivers (digital signage, apps, updates) so commuters can choose alternate routes or depart times — reducing unexpected gridlock.

• Coordinate with transit + promote alternatives to single-occupancy driving

Encourage improvements to public transit and active transportation (cycling, walking), so some of traffic load is shifted off cars. (Thetransitalliance)

Facilitate and encourage flexible work arrangements / telecommuting or staggered work hours — this reduces peak-hour load. (Smart City)

For construction-heavy periods, offer more reliable transit options (bus reroutes, express buses) so commuting doesn’t rely solely on congested roads.

• Transparent communication, public-consultation and business/ resident support

Provide clear, advance notice of closures, detours and timelines — giving residents and businesses time to adapt (e.g. alternate routes, working hours). The city already does this, but when multiple projects overlap, communications can get lost. (CityNews Ottawa)

Offer support for affected businesses (e.g. easier load/unload access, signage, alternate parking) to mitigate economic damage from reduced traffic.

Engage communities early on — involve local feedback to shape when/how construction happens, especially in residential areas, to reduce safety concerns and local-traffic spillover.

• Improve internal planning and reduce red tape / delays in approvals

Fix the bottlenecks in post-approval processes for development / infrastructure plans, so projects can be spaced reasonably over time — rather than creating a backlog that triggers many works at once. The 2025 audit pointed to lengthy agreement-registration delays that contribute to clustering of construction activity. (Ontario Construction News)

Ensure departments coordinate better on scheduling, file tracking, and clear roles for decision-making to avoid unexpected delays or overlapping permits.

💡 What residents and daily commuters can do (for now)

Based on both expert suggestions and what’s coming up in Ottawa, here are some personal or community-level steps that can help mitigate the pain:

Use real-time traffic apps or check local construction maps before driving or biking — plan alternate routes based on up-to-date detour info.

Consider flexible transit, cycling, walking, or carpooling — especially during major construction periods, to avoid being stuck in jams.

If safe and possible, shift travel times (e.g. avoid rush hour), or combine errands to reduce trips.

Give feedback to local councillors / community reps if construction impacts your neighbourhood or business — public pressure can push for better coordination and mitigation.

📊 The big picture: Ottawa’s stuck between a necessary catch-up and poor execution

Ottawa — like many growing cities — is in a phase where decades-long infrastructure needs (roads, sewers, transit) are finally being addressed. That’s good and necessary. But the downside: when too many projects collide in time and place, without strong coordination, the day-to-day cost falls on residents — long commutes, transit delays, frustration, and wear on local businesses.

If we want to continue upgrading the city — while protecting quality of life — it requires better planning, smarter execution (using technology + adaptive work zones), and more alignment between departments, residents, and businesses.

Question: Why should we cancel Lansdowne 2.0 in Ottawa?

Here’s a breakdown of why many people argue we should cancel Lansdowne 2.0 in Ottawa — and the main criticisms of the plan. (If you like, later I can also walk through alternatives to Lansdowne 2.0 that people propose instead.)

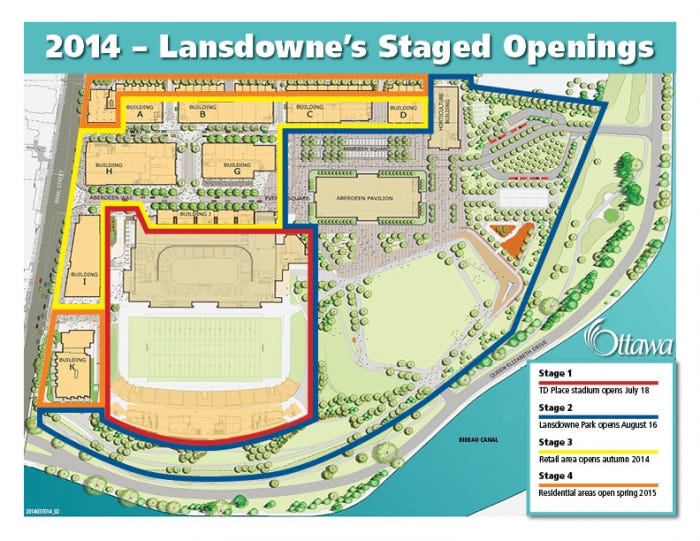

❓ What is Lansdowne 2.0

Lansdowne 2.0 is a redevelopment proposal for Lansdowne Park that involves tearing down and rebuilding parts of the existing facilities (arena / event centre, north-side stands), building new residential towers, and reworking retail / commercial space. (City of Ottawa)

Proponents argue it modernizes aging infrastructure (the old arena is nearly 60 years old and reportedly reaching end of useful life), improves energy efficiency and accessibility, and leverages the land to generate revenue that helps pay for the redevelopment. (City of Ottawa)

But many critics now argue strongly against it — for several reasons.

🚨 Main Reasons People Say We Should Cancel It

● Cost, Risk and Uncertain Financial Return for the City / Taxpayers

The latest cost estimate for Lansdowne 2.0 has risen sharply — the project recently jumped from around $332 million to about $419 million. (CityNews Ottawa)

Some councillors and community‐groups argue the “financial model” relies on optimistic, speculative revenues (from condo/retail sales, event revenues, etc.) to pay the city’s long-term debt. (iPolitics)

The agreement is reportedly locked in — long-term, 50-plus years depending on private partner performance — which critics say transfers risk to taxpayers and makes it almost impossible to opt out. (A Better Lansdowne)

Some say these public funds would be better used elsewhere (e.g. transit, infrastructure, community services) rather than a high-risk entertainment/real estate gamble. (Ottawa Lookout)

● Loss of Public Greenspace, Community Character, and Social Value

The plan would eat into existing greenspace: roughly half of the “Great Lawn” and a popular berm would be removed to build the new arena. That greenspace currently serves as a public park, gathering place, concert space, and — in winter — a toboggan hill. (Ottawa Lookout)

The project also calls for high-rise towers and denser development on what many consider “park land.” Some residents argue this undermines the “park-ness” of Lansdowne and reduces recreational and public-use space. (Ottawa Lookout)

Many adjacent community associations — representing long-time residents — have voiced strong opposition, warning that it will alter the neighbourhood’s character, bring more traffic, congestion, and strain on local infrastructure, and reduce quality of life. (Ottawa Lookout)

● Reduced Venue Capacity & Risk to Sports / Community Uses

The proposed new arena/stadium capacity is being reduced compared to current facilities. This has drawn criticism especially from organizations such as Professional Women’s Hockey League (PWHL), which said they will not play at the new 2.0 arena — calling it “not viable.” (Yahoo Sports)

Critics argue that the reduced capacity undermines the utility of the venue for major events, sports, community gatherings — potentially limiting access and making tickets more expensive to recoup costs. (iPolitics)

Some say that rather than replacing functional (if aging) infrastructure, the city could invest in repairing and improving existing facilities — avoiding waste and preserving what works — especially given how limited the upside seems under the current plan. (Ottawa Lookout)

● Weak Public Support, Transparency, and Loss of Trust in Decision-Making

According to multiple surveys referenced by community-led groups: once details of the project are laid out (costs, green-space loss, capacity reductions), public support drops dramatically. One poll found that about 71% of respondents prefer maintaining existing buildings over replacing them. (nanos.co)

Another survey showed 65% oppose the current proposal in full, and 79% oppose any net loss of greenspace. (A Better Lansdowne)

There are also concerns over how transparently the city / private partner has negotiated the deal (particularly the financial risks, public debt obligations, long-term commitment). (A Better Lansdowne)

Many feel that the project was “rushed through” despite strong opposition from local residents, community associations, and civic groups. (Ottawa Lookout)

💭 What Cancelling Lansdowne 2.0 Could Achieve / What Would Be Lost by Not Proceeding

If cancelled:

The city could avoid hundreds of millions in public debt, and re-allocate limited public funds toward other urgent needs (transit, social services, affordable housing, infrastructure repairs, etc.).

Preserve existing greenspace, park character, and community-oriented uses of Lansdowne Park — rather than densifying and commercializing it.

Avoid the risk of venue disappointments: a smaller arena that fails to attract major events or sports tenants (as already signalled by PWHL).

Maintain trust in municipal decision-making and ensure future projects are built with stronger public consent, transparency, and alignment with community needs.

If we keep going (as 2.0 envisions):

There’s potential for modernization of old infrastructure and boosting revenue (though this is uncertain).

New housing and commercial development — but with questions about affordability, sustainability, and whether it serves existing residents or newcomers.

Given the many risks — financial, social, environmental, community — many argue that cancelling Lansdowne 2.0 is justified, especially in a city facing huge pressures on housing, transit, and infrastructure, where public dollars may be better invested elsewhere.

If you like, I can pull up 5–10 concrete arguments with data for or against Lansdowne 2.0 (for example: cost-per-resident, lost green space area, number of at-risk community users, alternate uses for funds). That might help you — or community groups — make a more evidence-based case. Do you want me to build that list for you now?

Yes.

Good — I can pull up a list of concrete arguments with data against Lansdowne 2.0 (or in favor of cancelling/rethinking it). Below are 8–10 of the strongest data-driven arguments often cited by critics.

📉 Concrete data-backed arguments against Lansdowne 2.0

1. Very high price tag & long-term debt burden

The total cost of Lansdowne 2.0 is estimated at $418.8 million. (CityNews Ottawa)

Even though the city claims the “net cost” to taxpayers is lower (≈ $130.7 million, or about 31% of total), that still represents a major expenditure — and commits the city to decades of debt repayment. (Councillor Allan Hubley)

Some critics argue the “real” cost will be higher once additional expenses — like parking, retail updates, contingency overruns — are included. (Capital Current)

According to analyses, if the project is delayed 10+ years, replacement costs for aging facilities could rise dramatically (estimated up to $752 million), but that projection itself depends on many uncertain assumptions. (Councillor Allan Hubley)

Implication: a large upfront public investment with long-term fiscal risk — especially if revenue or development assumptions don’t pan out.

2. Net loss of public greenspace — reduced park and public-use land

The plan removes about 58,000 square feet of existing public park (the “Great Lawn” / toboggan-hill / berm area) from public use. (heritageottawa.org)

The loss also includes removal of tree canopy (dozens of healthy mature trees), public-art installations (e.g. “Moving Surfaces”), and previously accessible recreational green space. (A Better Lansdowne)

The reduced greenspace comes at a time when densification is being proposed (residential towers for hundreds of new units) — meaning more residents and event-visitors but less outdoor public space per person. (shawnmenard.ca)

Implication: the “public-space to population/event traffic” ratio worsens — risking overuse, loss of amenity value, and long-term deterioration of park-space quality.

3. Reduced venue capacity and diminished utility for community / sports / events

Under Lansdowne 2.0, the redesigned arena and north-side stands will have less seating capacity than current facilities. (Ottawa Lookout)

Critics say that reduced capacity makes the venue less viable for larger events or leagues (e.g. professional women’s hockey), limiting long-term usefulness. (Ottawa Lookout)

Loss of features: the plan removes the roof over the north-side stands; the “berm” (natural-hill spectator space) will disappear; and public-viewing opportunities (from the hill / lawn) will be lost. (bulldogottawa.com)

Implication: despite large costs, the upgrade may deliver less utility (fewer seats/public-use options) than existing infrastructure, undermining event- and community-based value.

4. Weak public support and declining approval when details are known

In a recent survey commissioned by community-groups, 65% of respondents opposed the full Lansdowne 2.0 proposal as presented. (A Better Lansdowne)

Specifically, 79% opposed any net-loss of accessible greenspace. (A Better Lansdowne)

Another poll found that once people are informed of the full details (cost, reduced greenspace, smaller venues), support dropped sharply: from 64% “support/somewhat support” to 33%, and opposition rose from 28% to 60%. (Ottawa Lookout)

When asked directly, a large majority of respondents preferred maintaining existing buildings over replacing them (71% vs 18%). (nanos.co)

Implication: the project has poor legitimacy in the eyes of many residents — a serious concern when public land, community amenities, and long-term tax commitments are at stake.

5. Loss of cultural and community amenities — “throw-away” costs of relatively recent assets

The plan calls for demolition or removal of parts of the facility or infrastructure that were built or renovated recently (for example, retail built in 2014). Reports estimate ~$12 million worth of retail built in 2014 will be torn out. (A Better Lansdowne)

The redevelopment also entails the removal of public-art installations and other cultural amenities (e.g. the “Moving Surfaces” artwork), and elimination of public-viewing “berm” spaces that many residents valued. (A Better Lansdowne)

Community associations argue that this isn’t just replacing “old infrastructure” — it’s throwing away still relatively “fresh” public investments. (Ottawa Lookout)

Implication: the project destroys social/cultural value — not just aging, but usable, relatively recent amenities — for speculative gains.

6. Financial model depends heavily on speculative revenue and favourable assumptions

The city’s “net cost” calculation rests on several revenue streams that are uncertain, including sale of air rights, property-tax uplift from towers, municipal accommodation tax, rental income from partnership, positive cashflow projections, etc. (Councillor Allan Hubley)

If any one of those streams underperforms — e.g. condos don’t sell, event attendance is low, commercial/retail under-performs — the financial burden may shift back to taxpayers. Critics warn that the plan “locks the city into decades of risk.” (bulldogottawa.com)

Some estimates (from detractors) suggest “hidden” costs could push the total above $500 million — especially once parking, retail, contingency, or cost-overruns are factored. (Capital Current)

Implication: the financial viability is precarious — success depends on “best case” scenarios; downside risk threatens public finances if assumptions fail.

7. Lack of meaningful affordable housing or social benefit despite densification

Although the redevelopment includes two residential towers with hundreds of units, the approved plan does not include any guaranteed affordable housing units. (CityNews Ottawa)

While city staff mention diverting some air-rights sale proceeds to affordable housing elsewhere, critics argue that’s insufficient — especially given the pressing housing crisis and demand for genuinely affordable units. (CityNews Ottawa)

Implication: the promised “housing benefit” is weak in practice, and the densification doesn’t guarantee social value or address affordability meaningfully.

8. Long construction timeline — extended disruption for residents and park-users

Critics project 7–10 years of construction for the full build-out (event centre, stands, towers, retail). (Ottawa Lookout)

During that time: loss of park access, reduced event-space utility, potential traffic/parking congestion on event nights, disruption for nearby residents, loss of amenity value for locals. (Ottawa Lookout)

Implication: even if the final project delivers some benefits — the trade-off is a long period of reduced quality of life for many residents, with uncertain payoff.

9. Environmental & ecological downsides — reduced green canopy, altered micro-climate, less ability for climate mitigation

The loss of large swaths of public green space, mature trees, and planned “green roof” (which was scrapped) reduces the park’s capacity for shade, storm-water absorption, heat-island mitigation, and biodiversity. (heritageottawa.org)

In a dense urban environment, preserving greenspace is a valuable public good — losing it undermines long-term environmental resilience. (shawnmenard.ca)

Implication: the project trades environmental and public-health value (green-space, tree canopy, ecological benefits) for commercial/real-estate development — a trade-off many find unjustified.

10. Loss of trust and public consent — legitimacy of the decision-making process is undermined

Many community associations and civic-heritage groups (e.g. Heritage Ottawa) have criticized the process as rushed, lacking transparent consultation, and skirting proper heritage / community-impact analysis. (heritageottawa.org)

Given the majority public opposition (once people understand the plan), bypassing or downplaying resident concerns risks reducing trust in municipal development decisions going forward. (A Better Lansdowne)

Implication: implementing Lansdowne 2.0 despite substantial public objection could have long-term political and democratic costs — setting a precedent of city-led “top down” developments without community buy-in.

⚠️ What these trade-offs would mean in practice (for residents / taxpayers / community)

Residents may end up with less public-use park space per capita, even if population / density increases, reducing the overall livability and green amenity value of the area.

The city carries a substantial, long-term financial risk — if projected revenue streams (air rights sales, tower sales, event revenues) underperform, taxpayers may have to cover shortfalls, or other services may be under-funded to service debt.

The “modernization” promise may be undermined by downscaled venues (less seating, no roof, smaller stands), which reduces the venue’s attractiveness for major events — meaning, in return for a large public expense, the net benefit for sports fans or event-goers could be lower than before.

Community and cultural amenities — green space, public art, informal gathering spaces, winter recreation (toboggan hill) — would be lost, potentially eroding neighbourhood character and reducing inclusive, public-oriented uses.

The long construction period means years of disruption: restricted park access, noise, traffic, parking/transportation headaches, and reduced utility for current users.

The lack of guaranteed affordable housing undermines one of the key justifications for densification, making the project potentially less socially beneficial than claimed.

✔️ Conclusion — Why these data-based concerns make a strong case for cancelling or rethinking Lansdowne 2.0

When you compare the scale of public cost/risk (debt, loss of greenspace, long build time, uncertain revenue) with the scale of promised benefits (some modern facilities, modest density, speculative revenue), the trade-offs appear highly skewed — especially given strong public opposition and weak guarantees (on affordable housing, capacity, environmental public-good).

In other words: the project asks Ottawa residents to pay — in money, green-space, community amenity, and long-term flexibility — for speculative private-market returns whose success is uncertain. For a city with urgent needs (housing, transit, infrastructure, social services), many argue these resources could be better spent elsewhere.

Question: How can Ottawa fix its LRT and transit system?

Great question — short answer: Ottawa needs a multi-layered fix that combines urgent safety & reliability remedies, better maintenance and governance, and re-shaping the network and policy so transit is fast, frequent and useful. Below I give a concise, prioritized plan (short / medium / long term) with practical actions and why each matters — based on recent Stage-2 updates, audit/follow-up activity, and OC Transpo reporting. (Ottawa Meetings)

Priority fixes (what to do, and why)

Immediate (0–6 months) — stop the bleeding, restore confidence

Make safety the top operational KPI and keep transparent dashboards.

Publish daily/weekly performance (on-time %, short turns, causes of delays) and a public action log so residents can see progress and staff are accountable. This reduces political heat and builds trust. (OC Transpo)KeepTemporary Speed Restrictions (TSRs) tied to clear engineering milestones.

Remove TSRs only after formal technical briefings and independent validation so “slow-running” doesn’t become the permanent norm. Council has already asked for technical briefings before removing TSRs. (Ottawa Meetings)Stabilize service with contingency fleets and bus bridging plans.

Ensure spare trains (or rapid bus substitution) are ready for single-train failures; formalize a rapid bus-bridging protocol and communicate it in advance so riders know alternatives. (OC Transpo)Fix communications and customer support.

Real-time alerts, clear detour maps, and a simple compensation/transfer policy for major disruptions restores rider goodwill.

Short–medium (6–18 months) — technical & operational resilience

Aggressive, independent maintenance audits and follow-ups.

Commission independent engineering reviews of track geometry, switches, support systems (overhead power, signalling/ATP), and make remediation mandatory with published timelines. The city’s audit/follow-up function is already doing related reviews that should be accelerated. (Auditor General of Ottawa)Address recurring technical failure points (power, track, switches).

Many major LRT systems see failures from “soft” track sections, poor drainage, overhead contact system vulnerabilities, and worn turnout components. Prioritize fixes (e.g., tamping, drainage remediation, insulating joints, turnout replacement) on the worst segments first so failures drop quickly. (This is a standard engineering priority after trial running and commissioning phases.) (OC Transpo)Improve contract & supplier management (RTM/rolling stock & contractors).

If certain vendors are underperforming, trigger contractual remedies, require root-cause-corrective-action plans, and attach performance incentives/penalties tied to reliability KPIs. Transparent performance clauses should be added to all major contracts.Professionalize operations staffing and training.

Increase simulator hours, emergency drills, and cross-skilling between lines so drivers and control staff can react faster to unusual events. Formalize a continuous-improvement program that logs incidents and closes corrective actions.Protect maintenance windows and invest in spare parts inventory.

Reserve overnight/weekend blocks for preventive work and boost critical spare parts stock (switch motors, power components) to reduce multi-day outages.

Medium–long (18 months–5 years) — system redesign & network improvements

Reconfigure bus network to be a true trunk+feeder system.

Rebalance routes so LRT + high-frequency bus trunks carry the largest volumes, while neighbourhood feeder routes provide reliable connections (and timed interchanges). That keeps buses from duplicating LRT unnecessarily and improves overall capacity.Transit Priority & signal priority across the city.

Faster buses (and better LRT interface) require aggressive transit signal priority, dedicated bus lanes on main corridors, and removal of pinch points caused by general traffic. This gives riders consistent time savings and makes the system competitive with car trips.Modernize control & signalling (ATP, CBTC or equivalent upgrades).

Invest in modern train control that supports closer headways, automatic protection, and better fault isolation. This enables higher frequency, safer operation, and faster recovery from incidents.Integrated fare & service incentives to grow ridership.

Simplify fares, implement fare capping or better transfer rules, and run targeted promotions (off-peak discounts, employer partnerships). More riders spread fixed costs and improve system economics. (Capital Current)Robust oversight — independent technical advisory panel and regular public audits.

Create a permanent expert panel (engineers, operations specialists, user reps) to review technical plans, procurement, and reliability reports. Use the Auditor’s follow-up process to track progress publicly. (Auditor General of Ottawa)Stage-gating for future expansions.

Tie future expansion openings (e.g., Stage 2 commissioning) to proven reliability on existing segments — e.g., maintain a public “readiness score” so extensions don’t double the number of failure points before the system is stable. Trial running and commissioning are necessary but must be validated with strong operational metrics before passenger service scales up. (OC Transpo)

System-level reforms (why they matter)

From firefighting to prevention: invest in maintenance and spare capacity so single incidents don’t cascade into multi-hour outages. Audits show problems when maintenance regimes and oversight lag. (Auditor General of Ottawa)

Better procurement ≠ cheaper procurement: include reliability KPIs and lifecycle cost (not only upfront price) in contracts so suppliers are accountable for long-term outcomes.

Network thinking, not line thinking: buses, LRT, active transport and demand management must be planned together — that’s how you get net travel time reductions and higher ridership.

Quick “scorecard” — how we’ll know it’s working

On-time performance for LRT ≥ 95% (daily tracked public metric).

Mean time between service-affecting failures increases 2× in the first year.

Spare train availability ≥ 8% of fleet (or formal rapid bus-bridge activated within 20 minutes).

Customer satisfaction up 20% and ridership stabilizes/grows.

Independent audit finds ≥ 80% of remedial recommendations completed on schedule. (Auditor General of Ottawa)

Final note: politics, funding and public trust

Technical fixes need political backing and money. That means Council must prioritize transit maintenance in budget decisions, resist short-term cuts, and demand transparent, accountable reporting to the public. Several city processes (Transit Committee briefings, Auditor follow-ups, Stage-2 readiness reports) are in place — use them aggressively to force progress. (Ottawa Meetings)